A celebrated early noir that is essentially a police procedural with a message about anti-Semitism. Somewhat disappointed in this one; time has diminished its impact.

A celebrated early noir that is essentially a police procedural with a message about anti-Semitism. Somewhat disappointed in this one; time has diminished its impact.

It's a good-looking flick. Directed by Edward Dmytryk, with cinematography by J. Roy Hunt, the movie makes a virtue of stripped-down minimalist sets and lighting designed to look like it is coming from real-world sources. The alternating angles in certain sequences, like the savage beating that opens the movie, are striking indeed. Robert Ryan is superb of course, but John Paxton's script leaves his character pretty one-dimensional, an anti-Semite with no background, explanation or even other characteristics, aside from cunning and sadism. Mind you, that is quite realistic in itself. Raging bigots in real life frequently don't have "reasons;" they simply are shits. Movies, however, thrive on fleshing things out, and Ryan's obvious dreadfulness allows the audience too much distance from his bigotry.

Robert Young was as good as he could be with the policeman character, quietly waiting for Ryan to hang himself. The Siren often finds Young underrated. Not much he could do with a lengthy speech about prejudice, however. It involves Young's Irish grandfather and the bigotry he faced, and the Siren wasn't quite sure of the point: "Oh my GOD! you mean they discriminated against CHRISTIAN WHITE PEOPLE too?" Seemed sufficient to the Siren that the victim was killed for being Jewish. Even in 1947, did they have to drag larger segments of the audience into the Great Oppression Sweepstakes so they would understand that this was wrong? Perhaps so, the Siren afterthought, as she recalled that same year's Gentleman's Agreement, in which we learn about anti-Semitism by watching a Gentile suffer from it.

It is mentioned often, but worth noting again, that in the novel Crossfire is based on, the victim was a homosexual. He was changed to a Jew to get past the censors. In the movie, despite the presence of a girlfriend, the murder victim gives a distinct impression of picking up a young soldier in a crucial early scene in a bar. Doubtless this did not register with many 1947 audience members, but the Siren still thinks it was deliberate.

Ryan's guilt is telegraphed early and the script does only a so-so job of stretching out suspense concerning his fate. Instead of furthering gripping the audience, developments like a sequence involving Gloria Grahame playing (what else) a floozy just seem like padding. The Siren's favorite part of the movie was Robert Mitchum, whose presence is a touch ironic considering some intemperate anti-Jewish remarks he made when well into his sunset years. But here he looks great, sounds great and does a lot with a smallish part that is also somewhat underwritten. The Siren will long treasure the look Mitchum gives his own shoulder, seconds after Ryan's character has given it an unwelcome, brotherly pat.

- Actors and Acting (55)

- Alfred Hitchcock (7)

- Alida Valli (1)

- American Idol Wins Gold During Sweeps Month (1)

- Anecdote of the Week (26)

- Audrey Hepburn (4)

- Ava Gardner (7)

- Baghdad and Boobs (1)

- Barbara Stanwyck (12)

- Basil Rathbone (4)

- Bette Davis (15)

- Billy Wilder (12)

- Blogathons (18)

- Brian Aherne (2)

- But You Cant Quit (1)

- Charles Boyer (5)

- Charles Laughton (10)

- Charlie Chaplin (6)

- Come On Down (1)

- Constance Bennett (10)

- crabby dissent (11)

- Culture-lite. (1)

- Cyd Charisse (4)

- dance on film (8)

- David Hemmings (1)

- David O. Selznick (10)

- Douglas Sirk (9)

- Ernst Lubitsch (10)

- Family Drama Ya Little Maggot (1)

- For the Love of Film (11)

- Foreign Film of the Week (4)

- foreign films (6)

- Frances Farmer (2)

- Frank Borzage (8)

- Fred Astaire (3)

- Fritz Lang (5)

- Gene Kelly (6)

- Gene Tierney (7)

- George Cukor (11)

- George Sanders (11)

- Ginger Rogers (7)

- Gone with the Wind (3)

- Hedy Lamarr (6)

- Howard Hawks (9)

- Humphrey Bogart (4)

- Ida Lupino (8)

- in memoriam (17)

- Ingrid Bergman (4)

- Inkspot today (1)

- IT'S ALIVE (1)

- Jack Cardiff (5)

- Jack Carson (7)

- James Cagney (9)

- James Mason (2)

- James Stewart (4)

- James Wong Howe (10)

- Jean Negulesco (6)

- Jean Simmons (1)

- Jennifer Jones (1)

- Joan Crawford (11)

- Joan Fontaine (18)

- John Barrymore (17)

- John Ford (8)

- John Garfield (8)

- Josef von Sternberg (3)

- Joshua Logan (1)

- Kay Francis (6)

- Kimber's Kraziness (1)

- Lana Turner (3)

- Leslie Caron (2)

- links (2)

- lists (18)

- Little Girl - WOW (1)

- Luise Rainer (2)

- Marilyn Monroe (3)

- Martin Scorsese (1)

- Mary Astor (8)

- Maureen O'Hara (3)

- Max Ophuls (9)

- Merle Oberon (2)

- Michael Curtiz (2)

- Michael Powell (4)

- Miriam Hopkins (1)

- Mitchell Leisen (4)

- Montgomery Clift (2)

- Movie Books (11)

- movies in brief (17)

- movies in depth (34)

- Mr. Uncertain (1)

- Music . I Know (1)

- Musicals (6)

- Myrna Loy (8)

- New York City of the Mind (10)

- Norma Shearer (3)

- Orson Welles (6)

- Oscars (11)

- polite dissent (12)

- Preston Sturges (5)

- Prince Poppycock on America's Got Talent (1)

- Production Code (8)

- Raoul Walsh (1)

- Robert Wise (1)

- Samuel Goldwyn (8)

- Sandra Dee (1)

- Shadows of Russia (9)

- Silent Movies (8)

- Simone Simon (1)

- Step Into an Enchanted World (1)

- Stop Filming Me (1)

- Sweet Home (1)

- Sydney Greenstreet (9)

- TCM (37)

- That Rhymes and that Stands for Pool (1)

- Thoughts on Fatherhood. (1)

- Val Lewton (1)

- Vera Zorina (2)

- Vincente Minnelli (3)

- weblog awards (2)

- William Wellman (7)

- William Wyler (13)

- Writing (1)

- You Can Puke (1)

Followers

(This marks the Siren's slightly belated contribution to Goatdog's 1927 Blog-a-thon, which was this past weekend. Please follow the link to Goatdog's place and read the other contributions as well, for a wonderful trip in the 80-years-back machine.)

(This marks the Siren's slightly belated contribution to Goatdog's 1927 Blog-a-thon, which was this past weekend. Please follow the link to Goatdog's place and read the other contributions as well, for a wonderful trip in the 80-years-back machine.)

Why is the word "modern" considered an accolade, much less the word "realistic"? When she wants modern, the Siren watches modern. Most of the time, the Siren prefers old-fashioned things, like romance and superimposition shots and duels filmed in silhouette. There are times when it is a good thing to show your age. When you're a bottle of vintage port, for example, or when you're a rare manuscript, or when you are 61 years old but, by God, you are Helen Mirren. And, the Siren would argue, it is a fine and glorious thing to show your age when you're a silent movie like Flesh and the Devil. Very little of this movie's atmosphere or plot smacks of 1927 (or 1926, when it was filmed) and in fact there are some decidedly 19th-century aspects to it. The clothes are 1920s-looking, but the rooms are lit by candles, people travel via horses and the settings are military boarding schools, castles and the like. To put it mildly, there is a lot of baggage attached to this one. Baggage, hell, it drags a freight train full of Hollywood history, foreshadowing and hindsight into your living room the second you hit "play." This lavish MGM production was made to showcase the pairing of their most valuable male star, John Gilbert, and their soaring new female star, Greta Garbo. When Flesh and the Devil was released in early January 1927, The Jazz Singer was only 10 months away.

To put it mildly, there is a lot of baggage attached to this one. Baggage, hell, it drags a freight train full of Hollywood history, foreshadowing and hindsight into your living room the second you hit "play." This lavish MGM production was made to showcase the pairing of their most valuable male star, John Gilbert, and their soaring new female star, Greta Garbo. When Flesh and the Devil was released in early January 1927, The Jazz Singer was only 10 months away.  The release of His Glorious Night, the movie that all but ended John Gilbert's career, was just two and a half years in the future, and in less than a decade Gilbert would be dead--of a broken heart, said his friends; of cardiac arrest brought on acute alcoholism, said the doctors. Garbo, for her part, was just three films into a Hollywood career that would defy all attempts at comparison, then or since.

The release of His Glorious Night, the movie that all but ended John Gilbert's career, was just two and a half years in the future, and in less than a decade Gilbert would be dead--of a broken heart, said his friends; of cardiac arrest brought on acute alcoholism, said the doctors. Garbo, for her part, was just three films into a Hollywood career that would defy all attempts at comparison, then or since.

The movie also began their celebrated love affair, though some maintain that was more image than reality. Maybe. For those who argue Gilbert-Garbo was the real romantic deal, Flesh and the Devil is mighty strong evidence. Gilbert caresses a flower stolen from Garbo's bouquet, Garbo purses her lips slightly to light a cigarette, they play a horizontal love scene as Garbo hovers over her man's face and kisses him with lips slightly parted. Eighty years on, the erotic charge between these two still flashes off the screen, despite the older acting style, despite the 1920s fashion for putting lipstick on a leading man.

Going strictly by the plot, the true love in the movie is between John Gilbert's character, Leo von Harden, and his best friend, Ulrich von Eltz, played by Lars Hanson. Their attachment probably draws some titters from "sophisticated" audiences unacquainted with eras when passionate declarations of love and fidelity weren't limited to those sharing a bed. It is a movie truth universally acknowledged, however, that two single men in possession of a good friendship must be in want of a vamp. So here comes Felicitas (Garbo, of course), ready to fascinate and seduce Gilbert from the moment he spots her at a train station.  They meet again, they waltz, they smoke and then they burn. Gilbert tosses a lit cigarette out the window, alerting Garbo's husband, Count von Rhaden (Marc McDermott), to the goings-on in his wife's boudoir. Husband? did she mention a husband? Gosh, no, she didn't, but there he is in the doorway, giving director Clarence Brown a marvelous shot--a Garbo-Gilbert clinch viewed through the wronged husband's outstretched fingers. A duel must follow, of course, and its filming is justly celebrated. We see it in long shot, the actors as silhouettes. Leo and von Rhaden march ten paces to the side of the screen, each stops just out of the frame, and we see two puffs of smoke.

They meet again, they waltz, they smoke and then they burn. Gilbert tosses a lit cigarette out the window, alerting Garbo's husband, Count von Rhaden (Marc McDermott), to the goings-on in his wife's boudoir. Husband? did she mention a husband? Gosh, no, she didn't, but there he is in the doorway, giving director Clarence Brown a marvelous shot--a Garbo-Gilbert clinch viewed through the wronged husband's outstretched fingers. A duel must follow, of course, and its filming is justly celebrated. We see it in long shot, the actors as silhouettes. Leo and von Rhaden march ten paces to the side of the screen, each stops just out of the frame, and we see two puffs of smoke.

Next shot ... Garbo, trying on mourning bonnets, the slightest of smiles on her face as she decides which veil is the most becoming. A perfect sequence, in 1927 or any other era.

Gilbert is exiled for five years. To protect the honor of Felicitas, he pretends the duel was about a dispute at cards. Hanson is enlisted to take care of Felicitas while his friend spends a few years in South Africa living in a hut. Okay, take a wild guess what happens next. Why, yes, that's exactly right. Hanson falls in love with Garbo, and they marry. Flesh and the Devil has many virtues; a surprising, twisty plot ain't one of 'em. So Leo comes back, but the love between him and Felicitas still burns. Leo is determined not to betray his friend, but Felicitas has other ideas.

Ah, this movie is lovely to look at, delightful to behold. Visual techniques of silent film were at an incredibly high point, about to plummet back to ground-bound staginess when the talkie craze took over. Shot after shot from William Daniels, who also lensed Greed and The Merry Widow, makes you want to pause the film and drink it in, whether it's a view across a frozen lake to an island with a man-made folly on it, or a simple close-up of Garbo's silk shoes, covered with snow. (Legend has it that the ethereal beauty had big, decidedly clod-hopping feet. To the Siren, Garbo's feet look fine, but her gams were no threat to Marlene.) Cedric Gibbons did the art direction and gave the interiors that certain fairy-tale look common to MGM's every depiction of aristocratic life.

Gilbert gets dissed quite a bit by modern critics, and the Siren isn't sure why. He is very dashing and handsome, less effete than Valentino if less menacing than Barrymore. As for Garbo, most critics note that she was sui generis, a brand-new type for the movies.  The Siren adds that this quality was Garbo's alone, not the script. Felicitas is written as a man-eating vamp like dozens of others in films of the era. It is the actress who conveys a soul behind the frippery. Favorite moment, for the Siren: Garbo nonchalantly touching up her lipstick, as a priest denounces her from the pulpit as a modern-day Bathsheba. Second-favorite, minutes later: the priest passes the communion cup, adjusting the rim to give each family member an untouched place to sip. Garbo stops him, turns the rim back to where Gilbert's lips had just touched it, and drinks from that spot. Her body and the angle of her head are perfectly ladylike and composed, but her expression of abandon is worthy of Salome. (Now there is a part Garbo could have torn up.)

The Siren adds that this quality was Garbo's alone, not the script. Felicitas is written as a man-eating vamp like dozens of others in films of the era. It is the actress who conveys a soul behind the frippery. Favorite moment, for the Siren: Garbo nonchalantly touching up her lipstick, as a priest denounces her from the pulpit as a modern-day Bathsheba. Second-favorite, minutes later: the priest passes the communion cup, adjusting the rim to give each family member an untouched place to sip. Garbo stops him, turns the rim back to where Gilbert's lips had just touched it, and drinks from that spot. Her body and the angle of her head are perfectly ladylike and composed, but her expression of abandon is worthy of Salome. (Now there is a part Garbo could have torn up.)

Among the cast is an ingenue named Barbara Kent, playing Hanson's sister Hertha. Her pure unselfish love for Gilbert must compete with the evil, manipulative Felicitas, and naturally Hertha doesn't stand a chance. She is rather charming, however, her tiny frame used to compose several amusing shots. She survived the talkie transition and made some other pictures, including the 1932 Vanity Fair and the 1933 Oliver Twist, then retired from the screen in 1949. Incredibly, she is still alive today, having turned 101 on Dec. 16. According to Wikipedia, she is one of only three prominent silent players still surviving, the others being Anita Page (age 96) and Dorothy Janis (who turned 97 on Feb. 19). Alas, Ms. Kent refuses all interviews. Still, it is wonderful to think that somewhere in Idaho there lives a link to the more sumptuous, romantic world of 1927 and this film.

The Siren is very, very hung up on proper writing and essay construction, and she sometimes forgets that this isn't what blogs are always about. So from time to time she plans to offer some brief takes on movies viewed over about a 20-month period. Inaugural post: The Bride Came C.O.D. (1941). Screwball well past its sell-by date, with two very, very great actors, Bette Davis and James Cagney, who simply didn't have the gossamer touch for this sort of thing. Bette Davis (who had just gotten married in real life) looks glowingly pretty, but watching her posterior plunk into a cactus plant--twice--feels like lèse majesté. From a distance of more than 60 years, you want to yell, "Bette! They can't treat you like that!" This time the talented Epstein brothers seem to have had no script ideas beyond "rough up the dame! it'll slay 'em!" They made Davis's character unbearable as well as unbelievable--the sort of spoiled heiress who finds herself in an airplane going someplace she doesn't want to go, and reacts by trying to parachute out. In high heels. Cagney has some appeal here, but his main job is to react to the heiress's latest piece of idiocy. Then he has to convince you he has fallen in love with her. He fails. The great Jack Carson, one of the Siren's pet character actors, gets almost nothing to do. Overall, a catastrophe.

Inaugural post: The Bride Came C.O.D. (1941). Screwball well past its sell-by date, with two very, very great actors, Bette Davis and James Cagney, who simply didn't have the gossamer touch for this sort of thing. Bette Davis (who had just gotten married in real life) looks glowingly pretty, but watching her posterior plunk into a cactus plant--twice--feels like lèse majesté. From a distance of more than 60 years, you want to yell, "Bette! They can't treat you like that!" This time the talented Epstein brothers seem to have had no script ideas beyond "rough up the dame! it'll slay 'em!" They made Davis's character unbearable as well as unbelievable--the sort of spoiled heiress who finds herself in an airplane going someplace she doesn't want to go, and reacts by trying to parachute out. In high heels. Cagney has some appeal here, but his main job is to react to the heiress's latest piece of idiocy. Then he has to convince you he has fallen in love with her. He fails. The great Jack Carson, one of the Siren's pet character actors, gets almost nothing to do. Overall, a catastrophe.

In preparation for Goatdog's 1927 Blog-a-Thon, coming up March 23-25, the Siren is posting some brief excerpts from a 1927 Vanity Fair article about Irving Thalberg. The article is by Jim Tully. One thing that strikes the Siren when reading film articles of the past is that the writers were often a great deal more prescient and perceptive than we give them credit for today.

He is considered a genius by many of the leading citizens of Hollywood. In the cinema world the word genius is more common than a threadbare plot...

I would have considered [Thalberg] a real boy wonder had he curbed with understanding the torrent that was Stroheim. For ... Stroheim is likely to be considered the first man of genuine and original talent to break his heart against the stone wall of Hollywood ...

To Thalberg, all life is a soda fountain. He knows how to mix ingredients that will please the herd on a picnic ...

He has inspired and sponsored such productions as The Big Parade, The Merry Widow, Tell It to the Marines, The Scarlett Letter, and Flesh and the Devil. He has been a firm rung in the ladder that led to the success of such stars as Lon Chaney, John Gilbert, Greta Garbo, William Haines and many others...

No person could dominate a world of cheap intrigue and fierce economics with a set of emasculated virtues. He can be relentless and suave. He can strike back from any angle. In a world where friendship is as shadowy as figures on a screen, Thalberg relies on no man. He has retained a level and a clear course through the helter skelter of the cheapest form of intrigue known to mankind--studio politics....

He is so wan, so tired-looking and so appealing, that women, ever on the alert to evade logic, often become sentimental about him. The feeling is wasted. Caesar Borgia was no better able to take care of himself...

The young supervisor's outstanding achievement for 1927 is Flesh and the Devil. The director, Clarence Brown, must be given full credit for this excellent film. He was ably assisted by the fine work of Greta Garbo. If Mr. Thalberg guessed these two people into their respective roles, which is quite likely, he should be given full credit...

In one respect Thalberg is superior to most producers. He reads books...

[quoting Thalberg] 'A young woman came to me from one of the fan magazines and said, "Mr. Thalberg--I realize that you are of the new order in films--a young man with ideals."

'I interrupted her. "If you mean that I think I'm superior to the so-called cloak and shoe and glove manufacturers who have really given their lives and their pocket-books to this business in order to allow us something to build on---why then--you are wrong. I respect them very much--they had ideals also." '

Above, Irving Thalberg and his wife, Norma Shearer, photographed by Edward Steichen in 1931. They really do look to be in love, don't they? For a look at the Thalbergs' celebrated beach house, go here.

Conventional wisdom about John Ford's The Informer goes something like this: The Informer is released,  wildly overpraised, wins Oscars for Ford and star Victor McLaglen. It spends a couple of decades on everybody's All-Time Ten Best List. Post-war, however, people look again, find it creaky, overwrought, and stickily sentimental about the ruthless IRA. Its reputation plummets, never to revive.

wildly overpraised, wins Oscars for Ford and star Victor McLaglen. It spends a couple of decades on everybody's All-Time Ten Best List. Post-war, however, people look again, find it creaky, overwrought, and stickily sentimental about the ruthless IRA. Its reputation plummets, never to revive.

It doesn't deserve that fate. The Siren saw a great print of it recently (on TCM--where else?) and fell in love. If you have not seen it, or if it has merely been a while, she urges you to give this movie a chance. The plot draws fire for its simplicity and obviousness, but all tragedies play out in an obvious, inexorable way, especially if they are classically structured like this one, observing unities of time and place and showing the inevitable consequences of a tragic flaw. The poetry of this tragedy isn't in the words, but in the images. The Informer is based on a novel by Liam O'Flaherty. In 1922, Gypo Nolan has been thrown out of the IRA for refusing to shoot a deserter. Now he is unemployed and desperate to escape to America with the woman he loves. (Screenwriter Dudley Nichols thus softened Gypo's motivation in the novel, which was poverty, nothing more.) To collect a reward of 20 pounds, Gypo reveals to the hated Black and Tans the hiding place of his friend, an IRA gunman on the run. His friend is killed trying to escape. The rest of the movie shows Gypo as he tries to escape both his own agonizing guilt and the certain revenge of the IRA.

The Informer is based on a novel by Liam O'Flaherty. In 1922, Gypo Nolan has been thrown out of the IRA for refusing to shoot a deserter. Now he is unemployed and desperate to escape to America with the woman he loves. (Screenwriter Dudley Nichols thus softened Gypo's motivation in the novel, which was poverty, nothing more.) To collect a reward of 20 pounds, Gypo reveals to the hated Black and Tans the hiding place of his friend, an IRA gunman on the run. His friend is killed trying to escape. The rest of the movie shows Gypo as he tries to escape both his own agonizing guilt and the certain revenge of the IRA.

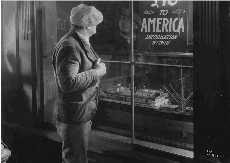

The movie's strongest claim to greatness is its stunning beauty. Over the years, anyone who watches enough movies grows accustomed to other filmmakers visually quoting Ford. Here, Ford appropriates a film vocabulary, that of German Expressionism, to flesh out the story without O'Flaherty's prose. The influence of M is everywhere, from the camera panning across a crowd to find Gypo's IRA pursuer, to a late trial sequence where Gypo's fear becomes almost physically painful to watch. The look of the film famously made a virtue of necessity, as The Informer was shot on a tiny budget on an RKO set that would have looked like flats from a high-school musical had it been lit like most Hollywood movies of the period. Instead, characters walk or stumble around a fog-shrouded Dublin that looks like a slum you dreamed on a bender. Via Joseph H. August's photography, light seems to physically struggle through the murk. The camera often takes Gypo's point of view, letting you see things the way a drunk sees them, with one person or image jumping into the foreground and the rest of it somehow dim. The images then shift the way they do in a clouded brain. Gypo approaches his love on the street, as she is wrapped in a shawl like a Madonna; she lowers the shawl, turns and as the light falls on her she is revealed as a prostitute. Shot after shot peers through a window or an entrance, as Gypo is on the outside looking in--at a poster for a voyage to America he will never take, through the doorway to his friend's wake, through another doorway to a shebeen where his blood money will buy him drink and the only pale imitation of respect he will ever know.

The look of the film famously made a virtue of necessity, as The Informer was shot on a tiny budget on an RKO set that would have looked like flats from a high-school musical had it been lit like most Hollywood movies of the period. Instead, characters walk or stumble around a fog-shrouded Dublin that looks like a slum you dreamed on a bender. Via Joseph H. August's photography, light seems to physically struggle through the murk. The camera often takes Gypo's point of view, letting you see things the way a drunk sees them, with one person or image jumping into the foreground and the rest of it somehow dim. The images then shift the way they do in a clouded brain. Gypo approaches his love on the street, as she is wrapped in a shawl like a Madonna; she lowers the shawl, turns and as the light falls on her she is revealed as a prostitute. Shot after shot peers through a window or an entrance, as Gypo is on the outside looking in--at a poster for a voyage to America he will never take, through the doorway to his friend's wake, through another doorway to a shebeen where his blood money will buy him drink and the only pale imitation of respect he will ever know.

The film alternates quiet with bursts of noise. Things begin in subdued late-night streets. Then Gypo's friend Frankie McPhillip (Wallace Ford) goes to see his mother and sister, and the paramilitaries burst in.  The scene becomes chaos, with the mother and sister screaming, grabbing the arms of the Black and Tans, throwing themselves in the way, trying anything to protect Frankie, as he tries frantically to get upstairs but wastes time yelling at them not to get in the way. Some see melodrama here. The Siren immediately recalled all the pictures we've seen from Iraq, showing the fear and mayhem of a house-to-house search. Frankie gets out to a barn loft, but is shot as he tries to cling to a beam. The camera follows only his arm, the rest of the shot filled with the British in the background, and the soundtrack records his nails scraping along the beam as he dies.

The scene becomes chaos, with the mother and sister screaming, grabbing the arms of the Black and Tans, throwing themselves in the way, trying anything to protect Frankie, as he tries frantically to get upstairs but wastes time yelling at them not to get in the way. Some see melodrama here. The Siren immediately recalled all the pictures we've seen from Iraq, showing the fear and mayhem of a house-to-house search. Frankie gets out to a barn loft, but is shot as he tries to cling to a beam. The camera follows only his arm, the rest of the shot filled with the British in the background, and the soundtrack records his nails scraping along the beam as he dies.

Later moments of quiet often come as we see Preston Foster's IRA commandant trying to catch the man who informed on Frankie. These scenes are often very beautiful--a tryst between him and Frankie's sister (Heather Angel), whom he loves, is played with only the fire in the fireplace as light. Alas, here the acting really does creak. Angel plays the hands-clasped, noble virgin, Foster the fists-clenched, noble lover. They are dull and at their worst, risible, as when Foster says "It's not me I'm thinkin' of. It's the others in the movement. It's Ireland." The Siren would love to posit that this contrast is deliberate, that Ford the artist wanted you to see Foster as a humbug and a bore. It is far more likely, however, that this part of the movie just hasn't aged well.  Indeed, the women in the film are its weakest aspect, though Margot Grahame does all right as Gypo's streetwalking love. "All the women in the story have been stereotyped into lay figures used to suggest the usual heart interests of commonplace fiction, and do not count very much," said contemporary reviewer reviewer James Shelly Hamilton.

Indeed, the women in the film are its weakest aspect, though Margot Grahame does all right as Gypo's streetwalking love. "All the women in the story have been stereotyped into lay figures used to suggest the usual heart interests of commonplace fiction, and do not count very much," said contemporary reviewer reviewer James Shelly Hamilton.

How much appreciation you have for The Informer may rest on your view of McLaglen's performance. The Siren simply thought he was great. There is a legend that he played the harrowing trial scene either half-drunk or viciously hung over, tricked into that state by his director. From her own brief stage training and everything she has ever read about acting, the Siren doesn't believe it. (The TCM link above also says Ford admitted in later years that there was no way McLaglen could have worked at his high pitch of emotion while actually drunk. Let us also note that Ford didn't need to get an actor drunk to terrorize him, as Maureen O'Hara could still attest. Anna at The Crowd Roars has something on Ford's rough way with actors as well.)

The Informer, and its title performance, form a pendant to the endearing, but utterly improbable stage-Irishry of The Quiet Man. Mind you, the Siren likes The Quiet Man, despite the objections raised by thoughtful viewers like the late George Fasel. The later movie is best viewed as a immigrant fairy tale, a fantasy of return to an Ireland of the mind.  But in The Informer, McLaglen is playing the dark side of his pugnacious, alcohol-sodden, none-too-bright screen persona. In The Quiet Man, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Wee Willie Winkie, he is supposed to be lovable. Here the actor plays, full-out, something much closer to what this sort of alcoholic is like in real life: loud, phony, self-pitying, prone to gusty over-dramatization, incapable of thinking past the next gulp of whiskey.

But in The Informer, McLaglen is playing the dark side of his pugnacious, alcohol-sodden, none-too-bright screen persona. In The Quiet Man, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Wee Willie Winkie, he is supposed to be lovable. Here the actor plays, full-out, something much closer to what this sort of alcoholic is like in real life: loud, phony, self-pitying, prone to gusty over-dramatization, incapable of thinking past the next gulp of whiskey.

Yet, as contemptible as Gypo can be, you retain sympathy for him. Later Ford films would show a man, often John Wayne, able to push back against the flow of history with nothing more than character. Gypo has no character, and no such ability. Ford shows you every one of his flaws, yet still treats him with compassion. Like Judas, Gypo throws his money away, this time on whiskey and a pitiful tart in a shebeen, fumbling for some sort of anodyne. You know he won't escape alive, but you yearn for Gypo to understand his own actions, so he can find the redemption he craves.

[NOTE: This last paragraph contains what could be taken as a spoiler for The Departed.]

In The Departed, Martin Scorsese used a clip from the end of The Informer, the climactic, crucifixion-like shot of McLaglen as he finally finds forgiveness. The Siren suspects that this moment, filmed precisely as Flaherty described it, would draw a laugh from a too-hip Film Forum audience. She also thinks Scorsese would not be giggling. It is a moment of real salvation, and by using it Scorsese shows there won't be anything like that for The Departed's characters. As the Catholic-bred Scorsese has illustrated in many films, to get redemption, you have to have real remorse. DiCaprio and Damon--even Nicholson, whose performance and fate give an echo of the Ford film--have only a rat's instinct for self-preservation. The Siren liked The Departed, but she is bold enough to think Scorsese wouldn't mind her preferring Gypo's end to his Boston counterparts.

(Postscript: In writing this piece, the Siren had a blast reading other bloggers' thoughts on Ford, including this by Lance Mannion. She has a lot of affection for that post because it was the first she read at Lance's place. There is this excellent post by fellow Ford admirer Zach Campbell at Elusive Lucidity, and also a fine appreciation of a Ford I haven't seen, Steamboat Round the Bend, at the blog Tativille. A while back, Andy Horbal posted a fascinating roundup of links about The Searchers, which just turned 50. If you need a corrective to all this Ford worship, try James Wolcott's thoughts, here.)

Cross-posted at Newcritics.

Come and Get It (1936) is a tale of the Wisconsin logging industry. Frances Farmer begins the movie as Lotta Morgan, a melancholy singing floozy at a loggers' beer hall, and ends it as Lotta Bostrom, the floozy's namesake daughter. Before we say anything else about this movie, from its two (actually three) directors to its mangled message, let's start by saying Farmer is good. Not fire-and-music good, but good. In the first half, directed by Howard Hawks, she is close to wonderful.

As Lotta Morgan, Farmer is pursued by Barney Glasgow (Edward Arnold), a buccaneer type you'd pick as a future tycoon even if you hadn't seen "based on a novel by Edna Ferber" during the credits. The actress is at her best in the beer hall, warbling "Aura Lee" in a warm contralto, working the room and shrugging off the wolves. At first she's only mildly interested in Barney and his pal Swan (Walter Brennan, with a Swedish accent that must have influenced Jim Henson). When Barney moves to outsmart a shell-game being run by the beer hall's owners, he has Lotta stand nearby for good fortune, despite Farmer's warning that she's bad luck (how's that for hindsight irony?). When Barney wins big, at first Lotta connives with the hall owner to slip the logger a drug and fleece him of his gains. But Barney treats her like a lady, not a tart, and Farmer touchingly shows how the logger's kindness makes her reconsider the plot to swindle him. She discards the Mickey Finn she had prepared, and in a brawling, funny scene that's so Hawks it hurts, Farmer, Arnold and Brennan bust up the hall in a hail of flying metal beer trays. (The scene looks dangerous, and probably was.)

But Barney's ambitions outstrip his love for Lotta. He courts Lotta, but he marries a lumber boss's daughter. Lotta turns to Walter Brennan for comfort. Let me type that again, in case it didn't sink in. Lotta turns to Walter Brennan for comfort. If nothing else convinced the Siren of Farmer's abilities, that scene would have. Not many actresses could make you believe that a woman would rebound to a man who says "Yumpin' Yiminy"--but Farmer accomplishes it.

So the first Lotta disappears, and Farmer's performance never has the same magnetism, though she is still pretty good. The movie takes a jump in time, and Barney is now married with two grown children. He goes to visit Swan and Swan's daughter by the long-dead first Lotta. Barney spots this second Lotta, also played by Farmer, and is bowled over. In a futile attempt to turn back time, Barney spends a lot of money trying to buy young Lotta's affections. She, in turn, falls in love with Barney's son Richard (a high-billed but underused Joel McCrea).

One problem with the second half is that Farmer as Lotta must protest that she has no idea, no, really, absolutely no idea that Barney sees her as anything other than a surrogate daughter. The actress is thus faced with the choice of playing young Lotta as either the biggest ninny in the Great North Woods, or a heartless wench conning an infatuated old man. Her solution is to play Lotta as very gifted in self-deception. It almost works, but not quite. She does have some good scenes later on, including one where she pulls taffy with McCrea. As directed in Hawks' inimitable style, this activity is both a nostalgic bit of Americana and suggestive as all hell.

Unfortunately for Farmer, late in the filming Hawks ran afoul of producer Sam Goldwyn. As Todd McCarthy relates in his biography, Hawks put off having Goldwyn see the rushes as long as possible. The director used Goldwyn's bout of pneumonia as one excuse, claiming he didn't want the producer to exert himself unduly. Eventually Goldwyn figured out something was up, saw the footage and took to his bed with a relapse.

Goldwyn biographer A. Scott Berg points out that the producer's reaction was somewhat justified. Ferber wrote a screenplay that was close to her novel, employing her usual device of viewing history as it affects one rags-to-riches family. Howard Hawks merrily ignored Ferber, hired frequent collaborator Jules Furthman to help with rewrites, and proceeded to film a Hawks movie: Two buddies have adventures as they both fall in love with a husky-voiced, strong-but-shady lady. Plus, the book has an environmental message that Hawks tries to ignore. All that's left is the screen crawl at the beginning, with a vague reference to robber barons who "took from the land and never gave back," and a later remark by Joel McCrea's character, that if his father had replanted the forests his current job would be a lot easier. Ferber was angry that her major reason for writing the book was tossed overboard, but she should have paid more attention to the early logging sequence. Even William Wyler said it was the best part.

The logging scenes were filmed on location in Idaho by second-unit director Richard Rosson. Please believe the Siren when she tells you that even if you have not the slightest interest in Farmer or her story, this sequence alone is worth renting the DVD or setting your TCM reminder. Huge trees are sawed down, falling amidst other trees still standing. Then the camera pulls back to where the trees are being dismembered for shipping, and the scale of the destruction becomes apparent. Massive logs piled several stories high are hit with blasts and roll, in enormous waves, down to where they will be shipped. One man seems to jump clear barely in time, in a shot that remains terrifying even after 70 years. Everywhere the snowy landscape is dotted with stumps. The logs are sent down a river clogged with sawdust and twigs and topsoil. The images combine the conquering swagger of a Hawks film with a panoramic view of man's wanton destructiveness. The catch is that the splendor of the logging scenes overwhelms the rest. The remainder is pretty good, but to equal the impact you'd need Eisenstein, not an uneven dual-generation family saga.

In any event, before Goldwyn even got out of bed, he had a frank exchange of views with Hawks, and Hawks was gone. Goldwyn called in Wyler, who didn't want to do it, for reasons ranging from professional courtesy to lack of affinity for the material. But Goldwyn threatened to put Wyler on contract suspension and take over Wyler's Dodsworth, then in its final stages. Wyler agreed.

Farmer was miserable. McCarthy relates that from the beginning she had given herself to Hawks' tutelage (a pattern he was to repeat, most notably with Lauren Bacall). To get the part in the first place, she had gone with Hawks into the Los Angeles red-light district to look at streetwalkers and study their movements and personalities. She wore her costumes at home to learn how to move in them, and worked with the director to ensure that even her voice was pitched differently for the two characters. Now she was faced with "90-take-Willie," and she hated him. "Acting with Wyler is the nearest thing to slavery," she said. McCarthy quotes Wyler's response: "The nicest thing I can say about Frances Farmer is that she is unbearable."

Figuring out where Hawks leaves off and Wyler begins is no trouble at all. About a half-hour from the end, the movie suddenly becomes rather restrained, and before you know it, there's a garden party going on. There is a father-son fight at the party, but it occurs in a drawing room and consists of just two blows. The fight was Hawks's idea, but the Siren thinks he would never have resisted the temptation to have Edward Arnold and Joel McCrea throwing each other over the flower arrangements. Farmer's character breaks up the fight, in what McCarthy points out is a foreshadowing of Joanne Dru's similar function in Red River. But Farmer's intervention is ladylike, not that of a strong woman telling two stubborn men to knock it off. The Hawksian woman has become an Edwardian doll.

All in all, Come and Get It does make for sad viewing, as Farmer's greatest director was also her biggest lost chance. Joel McCrea tartly remarked that Hawks "brought her on and then left her high and dry. Well, Hawks didn't care about anybody except himself." Farmer "inspired Hawks in his most concerted effort yet to create a feminine screen persona from scratch, and the early Lotta certainly stands as the first fully realized prototype of the Hawksian woman," writes McCarthy. But Frances never worked with Hawks again.

(Background on the filming of Come and Get It is from Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood, by Todd McCarthy, and from A. Scott Berg's Goldwyn. There is a nice collection of stills from the movie at this Frances Farmer fan site. The picture above shows Farmer as the young Lotta.)